Is Labour’s 2030 clean power mission still realistic — or is it time to rethink?

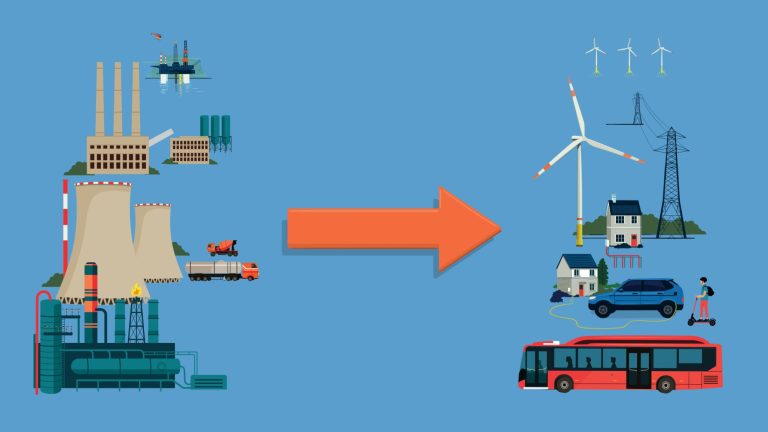

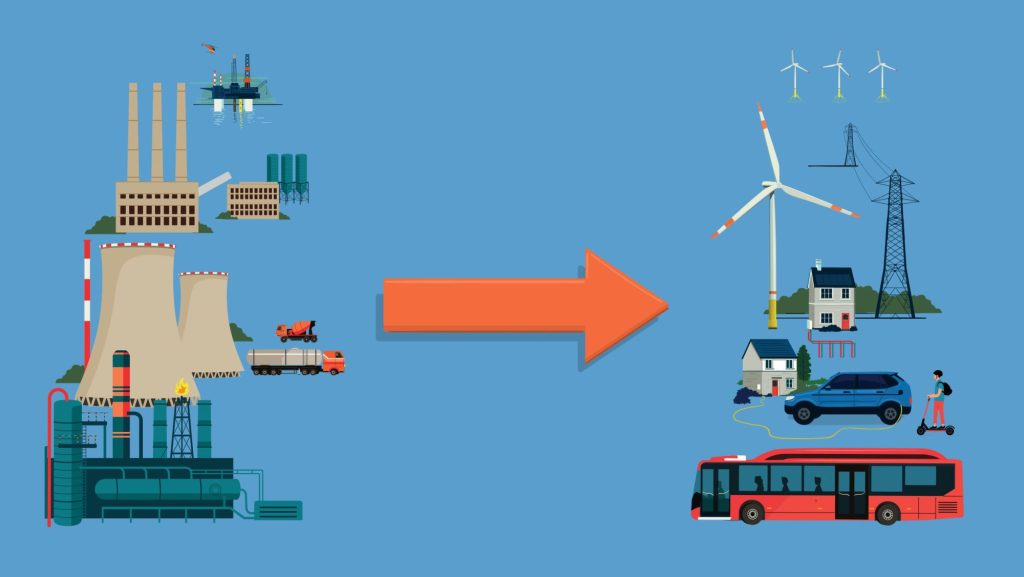

Labour’s commitment to deliver “clean power by 2030” has been a defining pledge: bold, headline-grabbing and designed to accelerate the UK’s transition away from fossil fuels. But as political and technical debates intensify, voices from across the spectrum are asking whether that target — once politically attractive and galvanising — remains the right policy lever for the task ahead.

Why the rethink conversation is growing

The criticisms come from unexpected quarters. The Tony Blair Institute has argued the target “was right for its time but circumstances have changed,” warning that pursuing the last few percentage points to hit a purely political milestone could have unintended consequences for costs and public support. Their line of argument is straightforward: voters care about bills and reliability far more than headline dates, and if decarbonisation is perceived to push up household energy costs or deliver unreliable supply, consent for net zero could fray.

Energy sector figures share parts of this scepticism. Some believe the 2030 goal was always more political than engineering-led — a target that has undeniably sped up consenting and planning, but one that may now need refinement to reflect system realities and to maximise emissions reductions and affordability.

What has the target achieved so far?

Supporters point to clear wins. The public commitment to 2030 has accelerated offshore wind auctions, sped up planning reforms and focused Whitehall on delivery. Energy UK notes the mission has “focused minds” and forced the removal of planning barriers that would otherwise have slowed renewables rollout. Recent auction successes — where capacity landed well above expectations — are offered as proof the policy is working to mobilise investment quickly.

In short: targets mobilise effort. They change incentives for developers, network operators and investors, and they create political momentum that makes hard choices in planning and consenting more tractable.

Where the tension lies: supply vs demand and the next phase

But the debate is shifting: having catalysed supply, the next big challenge is how to use that low-carbon generation to electrify transport, heat and industry in ways that cut overall emissions and — crucially — bring down bills. Analysts now say the policy priority should pivot from “build at any cost to meet 2030” to “optimise what we have built, ensure efficient system use and tackle demand-side electrification and flexibility.”

That means attention to networks, storage, demand management, smart charging for EVs, heat pump deployment and industrial electrification. It also requires ensuring the market structures and grid upgrades are in place so that new renewable capacity doesn’t create curtailment or system inefficiencies that undermine affordability.

Affordability and public consent

A recurring theme from sceptical think‑tanks and industry is the need to maintain public support. For many voters the bottom line is household bills and convenience. Perceptions matter: if the transition is seen as expensive, rushed or unfairly distributed, political backing will evaporate. The argument is that a “transition done right” must keep costs down and bring visible local benefits — jobs, investment and secure local supply — to keep people onside.

What ministers say

Downing Street and energy ministers remain publicly committed. Officials highlight the recent successful renewables auction and the stream of planning consents as evidence that the machinery is working and that the UK can still hit the mission. They argue that continuing to press the accelerator on deployment will lock in future cost savings and reduce exposure to volatile global gas markets — an argument sharpened by geopolitical risks and the instability of gas supplies internationally.

So should Labour relax the target? The pragmatic view

The emerging consensus among many practitioners is not to abandon ambition but to recalibrate emphasis. The question is not binary — meet the target at all cost, or drop it completely — but rather about sequencing and strategy:

Technical realities and policy design

Engineers and system operators stress that targets must be matched by granular delivery plans: clear timetables for network reinforcement, market signals for storage and flexibility, and local planning frameworks that expedite grid connection as well as generation consent. Cynicism about a top-line target often masks real technical challenges that need sustained policy attention.

What happens next?

The coming months will be critical. If planning and procurement continue to deliver above expectations, ministers will feel vindicated. If the supply-demand integration problems persist — for example, insufficient grid capacity, slow uptake of storage or lagging heat electrification — pressure will grow to adapt the target’s implementation and to emphasise the “how” rather than the “when.”