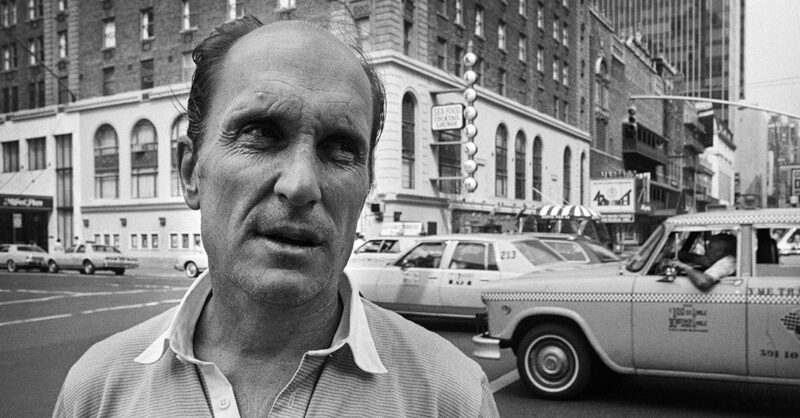

Robert Duvall: a master of stillness and a lifetime of understated craft

Robert Duvall’s work was never about spectacle. Across seven decades he became one of American cinema’s surest presences precisely because he practised a form of restraint that too many actors mistake for timidity. Put him in a frame and he filled the space not by volume but by authority: a measured breathing that made every line and silence carry weight. From his early, near‑invisible turn in To Kill a Mockingbird to the weathered men he embodied late in life, Duvall taught an object lesson in what acting can do when it stops trying to prove itself.

First impressions that last

For many viewers one of the earliest unforgettable images of Duvall comes from Apocalypse Now: Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore, sunburnt, immaculate in his cavalry hat, discussing napalm with a terrifyingly calm rationality. Coppola’s sequence is operatic—the helicopters, the Wagnerian music—but Duvall’s performance is the psychological fulcrum. Kilgore is not deranged spectacle; he is a composed believer. The serenity is what makes the violence credible and therefore more chilling. Duvall’s Kilgore anchors a film of grand gestures with a human centre whose composure suggests madness in all of its bureaucratic, institutional forms.

Training, theatre discipline and a craftsman’s patience

Duvall’s background explains a great deal about his approach. Born in 1931 into a naval family, he learned early the habits of discipline and movement through different posts and communities. He studied drama, served in the Army, and then trained in New York under Sanford Meisner at the Neighborhood Playhouse. This was the kind of education that framed acting as labour rather than gush: listening, responding, doing the detail work so that the whole could register as truthful.

His stage years were foundational. Theatre trains actors to hold silence, to be present when nothing happens—skills that translate to film as the ability to make a camera notice the interior life of a character without clouding it with mannered gestures. Duvall carried that schooling into his screen work. Even his smallest roles registered because he had learned to occupy space subtextually.

Small gestures, enormous returns

In The Godfather, Tom Hagen is a study in interiority. He’s the consigliere who inhabits legalism and loyalty without ever seeming theatrical about it. Duvall’s Hagen makes one believe in the moral architecture of compromise. There’s no raised voice; instead, a lawyer’s cadence and a strategist’s poise. That economy of means—saying everything with a lowered register of feeling—made Hagen one of the film’s moral anchors. Over the decades Duvall repeatedly chose roles in which restraint amplified a character’s moral or ethical tension.

Oscars and auteur projects—roots in authenticity

His Academy Award for Tender Mercies exemplifies his method. As a faded country singer, Duvall didn’t perform a caricature of decline; he inhabited the texture of a life grinding down and finding something like grace. Similarly, in The Apostle—his passionate, at times controversial, project as writer and director—Duvall probed the contradictions of faith, charisma and self‑deception with an intimacy that only a writer‑actor with deep empathy could sustain. He never sought applause for virtuosity; he preferred that the audience discover truth by degrees.

Aging on screen with dignity

Duvall’s later work is instructive on another front: how to age on screen. Rather than fighting time he allowed it to inform his performances. The voice grew rougher, the movements slower; yet authority deepened. It’s a lesson in how lived experience can be a resource for acting rather than an impediment. The authority of his later roles—men who carry histories and regrets—was gained substance rather than lost spectacle.

Consistency as craftsmanship

Over half a century Duvall returned to essentials: timing, restraint, attention. Directors seeking a performer who could hold a scene steady often cast him because he brought reliability and depth rather than a propensity to dominate. That steadiness made him adaptable: he could be the still centre in Coppola’s operatic world, the calm consigliere in Coppola’s dark fable, or an utterly private man in a quiet country film. What linked those roles was a refusal to let the machinery of cinema overwhelm character reality.

Why Duvall matters

In an era that prizes immediacy and often equates volume with importance, Duvall’s art insisted on a different metric: the power of the unforced moment. He demonstrated that restraint could create terror (Kilgore), decency (Tom Hagen), and heartbreak (the men of his later films). He modelled a career built on craft not celebrity—a line of work in which the job is to render the human condition precisely, compassionately, and without flattery.

Highlights and lasting impressions

Enduring legacy

Robert Duvall leaves a legacy not of headline‑grabbing bravado but of a discipline that privileged listening and truth. He was a craftsman whose performances were small machines of truth—precise, economical, and, in their own quiet way, devastating. For actors and audiences alike, his career is a reminder that cinema’s power often lies in its ability to hold still and let a human face do the work.